The seeds of a rich partnership with dogs formed thousands of years ago. Hunter gatherers who noticed behavioral variations in gray wolves, and nurtured the ones that showed favorable traits, did us all a great service.

Humans developed a skill for interpreting and translating dog behavior, and dogs learned to trust us. We learned how to work together.

Modern dog breeds have different aptitudes and tendencies. Of course, there are overlapping distributions of behaviors across breeds and variation within breeds. But what generalizations can be made about breed-typical behaviors and their origins?

Domestic dog lineages reveal genetic drivers of behavioral diversification1 is a paper that examines this question. The study used genetic data for over 4,000 domestic, semi-feral, and wild canids and behavioral survey data for over 46,000 dogs to do statistical analysis and trace correlations.

Statistics vocabulary

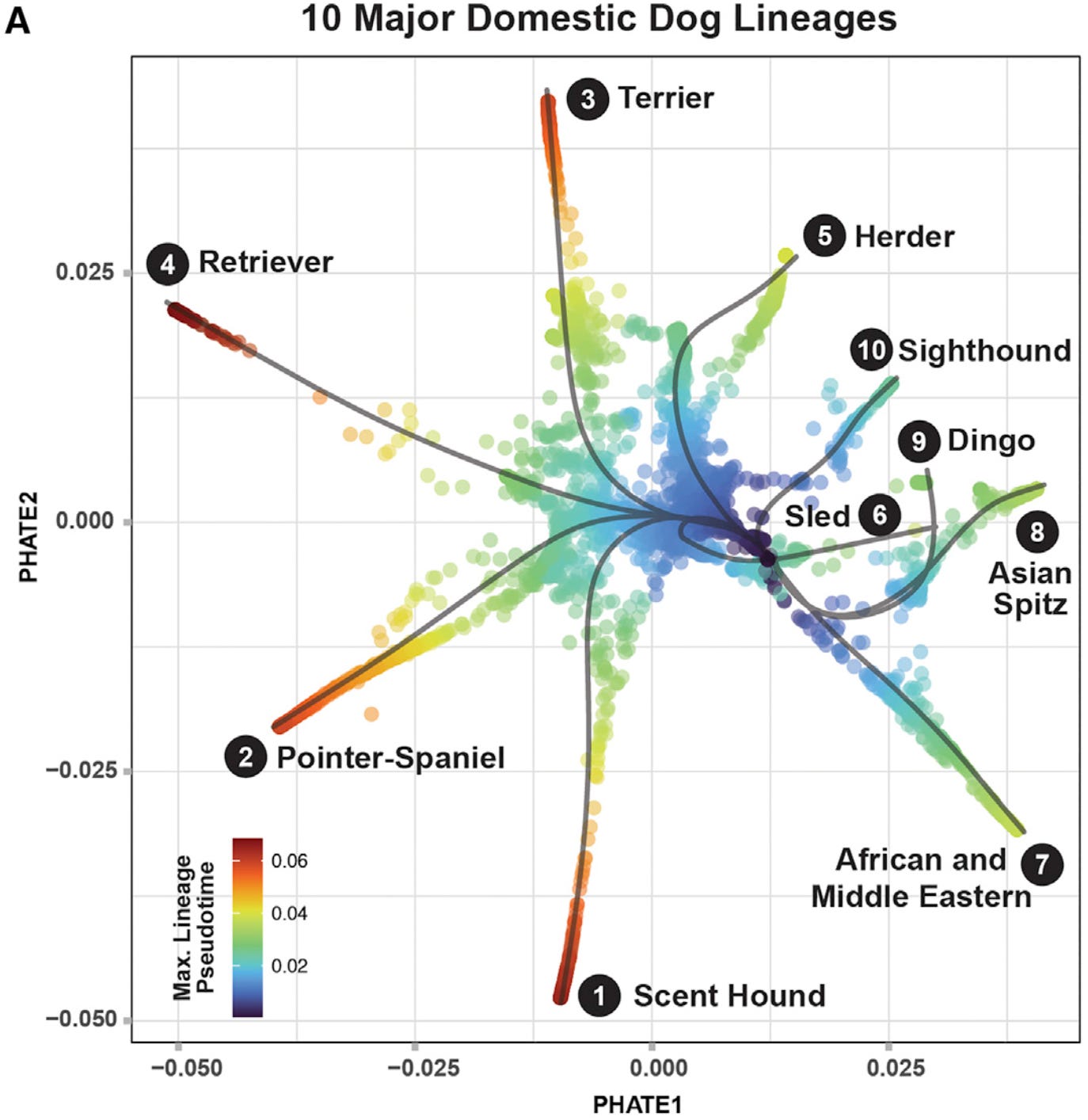

Dimensionality reduction is the statistics technique by which a heap of genetic features is reduced to two axis, PHATE 1 and PHATE 2 above. Wikipedia defines it:

The transformation of data from a high-dimensional space into a low-dimensional space so that the low-dimensional representation retains some meaningful properties of the original data.

The shape of this chart, the distribution of individual dots in a coordinate space, is a result of taking high-dimensional data, i.e. genetic profiles, of a bunch of dogs, and using statistics techniques to reduce it to a two dimensional representation.

The other statistics vocabulary word I want to highlight is pseudotime:

Short for pseudotemporal reconstruction. A method for inferring lineages among branching trajectories in high-dimensional data. [It is used] to cluster individuals into smooth lineages.

The highest pseudotemporal positions (otterhound and bloodhound) had the least amount of shared identity with all other dogs, while breeds with lower pseudotemporal positions generally showed higher shared identity with all other dogs.

Pseudotime is the basis of the color scale in the chart above.

Small-effect variants existed in gray wolves, and humans noticed. Over generations, they maintained domestic dog populations that keyed in on pre-existing behaviors. Selective breeding over thousands of years with relatively geographically isolated populations gave rise to behaviors like sled-pulling in the Arctic and livestock guarding in the Near East.

Dogs evolved into specialized hunting roles like scent vs. sight tracking, flushing vs. pointing, retrieving, treeing, and killing vermin. They also picked up jobs herding, pulling loads, guarding, and providing companionship.

Humans must have spent a lot of time observing canids to unlock so many possibilities in them. We owe a debt to many many old timers who built working relationships with our furry buddies.

Behavioral data

Nature is a great teacher. It turns out that the behaviors we came to depend on dogs for generally existed as variants before people started breeding them for aesthetics.

C-BARQ stands for the Canine Behavioral Assessment & Research Questionnaire2. It consists of owner-reported scores for 100 questions related to dog behavior, which are evaluated into 14 factor scores:

trainability

stranger-directed aggression

owner-directed aggression

dog-directed aggression

familiar dog aggression

dog-directed fear

stranger-directed fear

nonsocial fear

touch sensitivity

separation-related problems

excitability

attachment/attention-seeking

predatory chasing

energy level

By correlating C-BARQ scores and lineage pseudotime, researchers were able to generate behavioral distributions across breeds. Some of the interesting conclusions are:

Sheepdog-associated genes have been implicated in anxiety and maternal pup-gathering behavior in mouse models, suggesting that herding drive may involve augmentation of the same anxiety-associated pathways driving maternal protective behaviors in other species.

Terriers largely clustered…with predatory behavior and dog-directed aggression, while companion and toy dogs clustered…with increased social and non-social fear.

Herder, scent hound, and terrier lineages showed the most robust behavioral correlations, as well as…gene enrichment in…prefrontal areas of the cortex associated with human social cognition, decision-making, and emotional intelligence.

Acute sensitivity to specific stimuli is advantageous: herding dogs are keenly aware of subtle changes in the body language of livestock, terriers of…hidden prey, and scent hounds track the movements of game…[but these sensitivities also correlate to fear and anxiety behavior].

Great dog handlers will be familiar with most of these behavior patterns. A dog is out of balance when she needs a job and doesn’t have one, or thinks her job is x when it needs to be y. What stimuli is your dog sensitive to? What do they do with their energy when it spikes?

Every dog is unique, but experience and knowledge of breeds is helpful for reducing the time it takes for a handler to meet a new dog and understand them.

Dogs are at their best when they have opportunities to engage their innate drives, short of obsession, in balance with the communities we live in, around other people and dogs.

For more on dog training, check out ryanblakeley.net/p/dogs.

See original paper for graphics

Images used in this article are licensed from the publisher. The original study was fascinating. Graphics not reproduced in this article, but in the original paper, tell the story very well. If you get a copy (email the author for a free copy), see page 5 of 38:

A. The circular bar graph in the top left, represents how many genetic samples were used from each group. We have more genetic data from domestic dogs.

B. The color scale is labeled Gray Wolf IBS. It’s a one-dimensional score that compares each individual dog against gray wolf ancestry. The black cluster is gray wolves and coyotes.

C. This chart colors European origins. Notice in light blue the influence of Victorian era Great Britain accelerating breed divergence.

D. These charts compare breed origin and village dogs. Breed origin are samples in the dataset for ancestral dogs, and village dogs are modern free-breeding individuals that live around where people live.

https://vetapps.vet.upenn.edu/cbarq/about.cfm This explains C-BARQ and the 14 behavior factors.